Highland Park Senior/Youth Center Solar Islanding Study

Highland Park, NJThe Highland Park Senior/Youth Center was one of three potentials sites for community shelters studied as part of the Highland Park Solar Islanding Project (2015). The site fulfills at least some of the desirable traits of an emergency shelter and provides examples of community resiliency planning at the building level.

Why is it Important?

Superstorm Sandy affected Highland Park and many other places following its landfall in October 2012. Among the most severe impacts for Highland Park residents were electric power outages lasting up to two weeks for portions of the municipality. This experience highlighted a need to better prepare for similar situations in the future.

A set of adequately equipped community gathering spaces can support basic functions for community residents whose homes have lost power or are otherwise uninhabitable. Sheltered spaces are needed so that residents can rest comfortably, charge their phones, and have access to basic heating and cooking facilities enabled by resilient sources of electric power.

Solar arrays outfitted with battery storage and islanding inverters can provide emergency “power islands” during times of storm or other grid outages. When implemented in community meeting places that can function independently of the grid, solar islanding increases community resiliency. In the Highland Park Senior/Youth case study, the existing solar arrays if converted to solar power islands would be able ‘to provide only modest emergency’ power.

Available energy also depends on season and system engineering specifications. Thus, a critical step in planning for solar islanding capabilities is to analyze power demands and associated functions that benefit from solar islanding.

Figure 1 – Senior/Youth Center Site

For whom is this useful?

Because solar islanding has the potential to improve community resiliency, the following case study is most useful to municipalities and institutional building owners motivated to prepare community spaces for future power outages. Such institutional buildings might include schools and community shelters.

Summary of Location and Resiliency Characteristics: Youth/Senior Center

The Senior/Youth Center, located next to two senior housing apartment complexes, serves as a meeting place for local senior citizens and has a wide variety of social, recreational, and daily educational activities for the benefit and enjoyment of Highland Park Seniors.

A field visit to the facility (4/29/15 12:00 pm, sunny) confirms that it is a 1-story building and has ample parking right near its entrance. As one enters the building, there is a large hall on the left, currently utilized as a space for communal meals with subdividing electro-mechanical doors that can reconfigured for different events or activities, potentially serving as a community gathering space.

A natural gas-fired hot water boiler heats the building with electric circulating pumps (2 x 3/4 HP). Domestic hot water is also gas-fired. The kitchen has an electric stove, dishwasher, refrigerator, and microwave oven. It is unlikely to be able to operate without a substantial backup generator because of the electric stove.

Some rewiring is required to allow the Borough Hall & Fire Station solar arrays to serve the Senior/Youth Center. With about (28,560 + 6,012 = 34,572 W) 35 kW peak available, there is ample power available to charge cell phones, provide electric light (at a reduced level), and run the heating hot water circulating pumps. There may also be enough electricity to operate a microwave oven, but full-service food preparation and heating are likely not achievable, depending on the season and weather patterns.

Figure 2 – View of Senior/Youth Center from street entrance on S. 6th Ave.

Electricity Demand Calculation

Three questions were posed to determine critical electrical loads in the study:

- Must it be continuously available?

- Are there any affordable and convenient substitutes?

- What are the consequences for human health and economic costs?

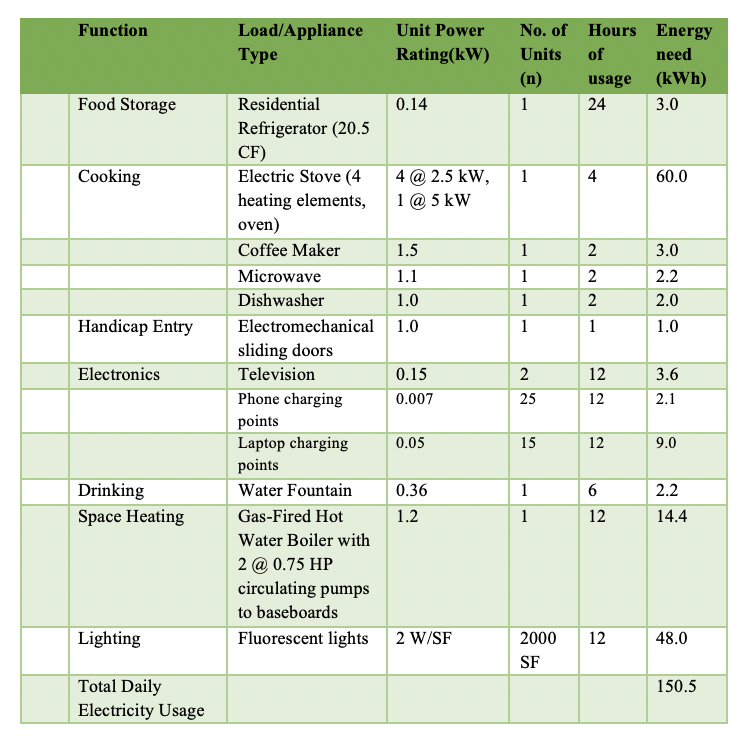

From interviews with the Senior Community Director, Ms. Kim Perkins, it is understood that the following electrical loads are critical to host any gathering of people comfortably and maintain the status quo of the facility’s operations (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Critical Electricity Load Calculation for the Senior/Youth Center

The numbers in Table 1 illustrate four important points that help to address the questions above concerning critical electrical loads. First, the all-electric kitchen contributes greatly to the electricity load in the Senior/Youth Center. Second, lighting, and to a lesser extent the relatively simple space heating system also significantly boost electricity demand. If lighting is used mostly at night, and the stove is parsimoniously used, the total electricity demand would drop significantly. This building is smaller than the other case study buildings and the solar arrays serving it (Borough Hall, Fire Station Parking Lot) are larger, so they may be able to supply adequate electricity even in winter. Third, heating, ventilating and air-conditioning (HVAC) energy requirements at the Senior/Youth Center (and most other) buildings are very large. During a power emergency, it may not be possible to operate these systems, at least not based solely on a solar+battery power source. Finally, charging cellphones and laptops is less of a concern because these devices do not consume much electrical energy. However, the ability to communicate to family members and loved ones during an emergency situation is important in supporting psychological well-being.

Funding Opportunities

New Jersey is committed to a renewable energy future, and incentives for renewable energy development often are available. For the most up-to-date information on renewable energy policy and incentive structures, visit the NJ Board of Public Utilities website http://www.bpu.state.nj.us/.

Cost Projections

A resilient system solution to enable sheltering capabilities at the Senior/Youth Center would combine substantial solar photovoltaic generation with reasonably sized battery storage on site, both of which are sizeable investments.

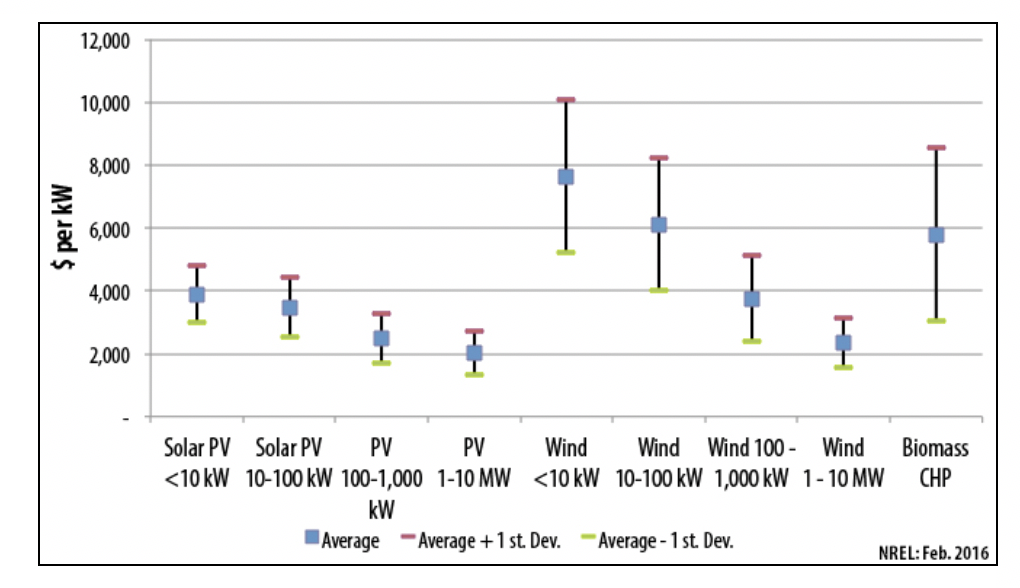

Figure 3 – Solar array installed costs for different system sizes (Source: NREL Energy Analysis. 2016)

Grid-tied solar arrays have a long history, and the costs have been coming down gradually with time, as competitive market factors have had their effect. Figure 1 shows recent (2016) data on costs for different kinds of renewable generation sources. The most relevant match to the systems Highland Park might consider would be the “PV 100-1,000” data point, which translates to about $3.5 to $4 per Watt, installed. This price includes the inverter, fixtures, and wiring. Parking structure arrays are probably a somewhat higher cost as they involve very sturdy designs intended to withstand very high winds. These systems might be $5/W or more, depending on the configuration.

Battery systems installed to provide resilient power backup have less track record. Also, retrofit projects added onto existing solar require an upgrade to the existing power inverter for the system. Newer inverters can provide the islanding capability not designed into the earlier New Jersey installations.

Resources

Highland Park Solar Islanding Project (2015). Prepared for the Borough of Highland Park, NJ by Jennifer Senick, Executive Director, Rutgers Center for Green Building; Dunbar Birnie, Professor of Ceramic Engineering, Department of Materials Science and Engineering; Aman Trehan, Research Graduate Assistant; Nan Chen, Research Graduate Assistant; Deborah Plotnik, Program Coordinator, Rutgers Center for Green Building, Rutgers – The State University of New Jersey.

Related Strategies

- Combined Heat and Power (CHP)

- Demand Response and Peak Load Management

- Emergency Water Supply and Storage

- Energy Star Equipment and Plug Loads

- On-site Renewable Energy Systems

- Roof Replacements and Upgrades

- Smart Metering

- Solar Islanding and Micro-Grid Ready Solar PV

- Storm Preparation and Emergency Planning

- Thermal Energy Storage