Vegetated Roof

New ResidentialWhat is a Vegetated Roof?

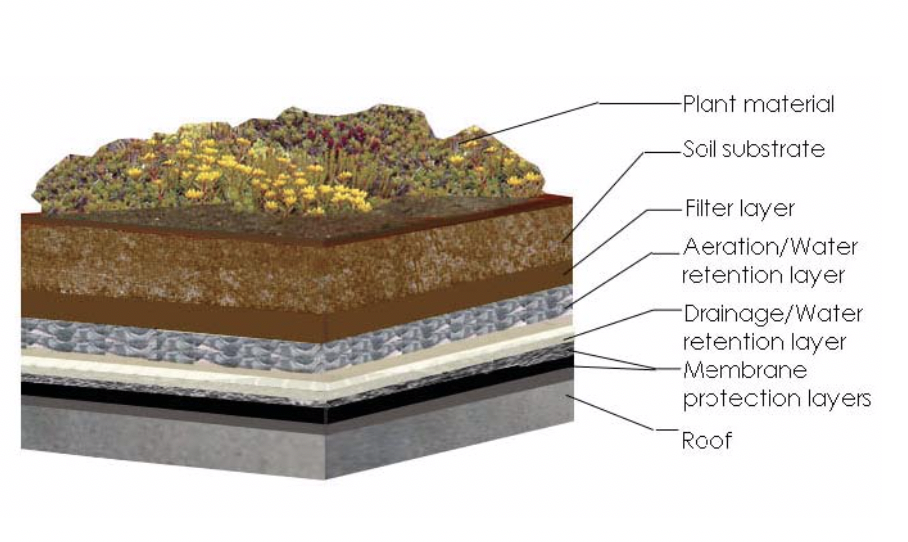

A vegetated roof or green roof consists of vegetation in a lightweight growing medium placed on top of the drainage layer, root barrier, and waterproof membrane (see Figure 1). Vegetated roofs provide many environmental benefits such as decreased stormwater runoff and reduced building energy use. They absorb air pollutants and provide a habitat for beneficial insects and birds, serve as a sound barrier, and mitigate the urban heat island effect.

Figure 1: A basic cross-section of a vegetated roof (Source: New York City Department of Design & Construction Cool and Green Roofing Manual).

How to How to Incorporate a Vegetated Roof

There are many pre-engineered green roof systems available on the market, but green roof designs are often customized to achieve a project’s specific performance objectives. Consult a design professional and integrate the development of the green roof with the development of the building’s structure and systems. The roof strength must be able to hold 10-25 pounds per square foot above the requirements of an underlying roof.[1]

The two primary categories of vegetated roofs include: extensive and intensive. Extensive vegetated roofs consist of lightweight systems with shallow soil (or other growing media) depths usually less than 6 inches.[2] Extensive vegetated roofs require less structural support than an intensive system and support a more limited palette of hardy plants adapted to extreme environments that need little maintenance. Intensive vegetated roofs typically have more than 6” of soil or other growing media, weigh more than extensive vegetated roofs, and can support a greater variety of plants. Intensive systems require more maintenance and a higher initial investment than an extensive roof.[3]

Vegetated roofs can host a variety of plant species but typically include drought-tolerant species such as hardy succulents, sedums, and perennials. Consider low-maintenance, native species capable of living in the shallow soil. For a list of species indigenous to the Northeast, see NYC Greenbelt Native Plant Center or List of NJ Native Plants by County.

Vegetated roof requires some maintenance such as watering during the establishment period and occasional weeding. Seasonal pruning and cutting of grasses and annual plants reduce the accumulation of combustible material on the roof. Regularly inspect and maintain the components of the roof’s drainage system such as gutters, underdrains, and downspouts.[4]

Example

Homeowners installed a vegetated roof, consisting of a system of trays holding a lightweight growing medium and drought resistant sedums, to reduce energy consumption and add aesthetic value. [5]

Benefits

Reduced Stormwater Runoff

A vegetated roof can reduce stormwater runoff through retention and evapotranspiration and by slowing the release of precipitation, resulting in reduced peak flows in a watershed and reduced stress on municipal stormwater infrastructure.[6]

Reduced Urban Heat Island Effect

The evapotranspiration provided by vegetated roofs reduces both the temperature of the roof and the surrounding air temperature.[7] Vegetated roofs can remain 30-40% cooler than conventional roof surfaces, contributing to an average energy savings of 0.7% compared to non-vegetated roofs (see Cool Roofs).[8] Several vegetated roofs in the NYC region were monitored to collect data about vegetated roofs and the urban heat island effect through the Columbia University’s Center for Climate Systems Research and the data collected help document the role that vegetated roofs can play in mitigating the urban heat island effect.

Reduced Air Pollution

Green roofs serve as a carbon sink, helping to offset carbon emissions. Vegetation traps dust and particulate matter as well as other contaminants such as nitrogen oxides.[9]

Energy conservation

The multiple layers of a vegetated roof provide insulation (see Insulation). By increasing a building’s thermal mass, vegetated roofs can help keep temperatures cool in hot weather and warmer during the heating season translating into less energy spent on climate control for the building (see Thermal Mass).[10]

Increased Wildlife Habitat

As the roof system matures, a mini-ecosystem, which supports a variety of beneficial insects, butterflies and birds can develop increasing biodiversity and providing a habitat for native wildlife (see Native and Adapted Plants and Wildlife Habitat).[11]

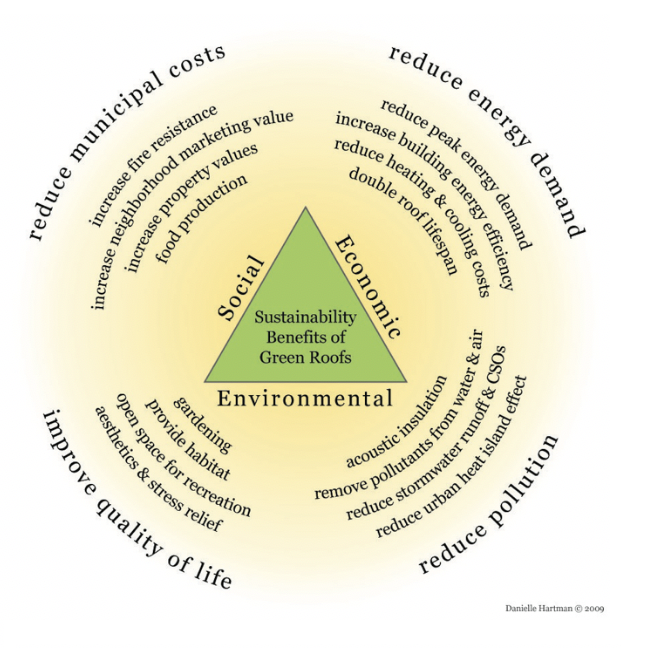

Improved Quality of Life

Like other urban greenery, vegetated roofs provide many intangible benefits for people. Installing a vegetated roof can be a method for integrating more green space into the site and the community. Also, neighboring buildings may gain a bonus view of nature when located near a building with a vegetated roof (see Biophilia).

Figure 2 – Benefits of Green Roofs (Source: Hartman, Danielle. Poster presentation, ESRI International User Conference, San Diego. July 2009).

Costs

According to the US EPA, estimated costs of installing a green roof average $10/sf for extensive roofing, and $25/sf for intensive roofs. Maintenance costs vary for either type of roof and may range from $0.75–$1.50/sf.[12]

Changing temperatures and UV rays decrease the quality and life of a roof. Vegetated roofs protect rooftops and its structure, decreasing maintenance. Long-term savings from reduced heating and cooling costs and reduced maintenance can help offset the short-term capital costs.[13]

Resiliency

Vegetated roofs can provide thermal insulation throughout all four seasons, reducing energy consumption and reliance on the electrical grid. In the event of a power outage, they can help keep temperatures cool in hot weather and warmer during the heating season. During heavy rainfalls and flooding events, vegetated roofs can help reduce stress on municipal stormwater infrastructure and reduce combined sewer overflows.[14] Vegetated roofs can also offer local communities the opportunity to grow some of their food, reducing dependency on supply chains and transportation networks often disrupted or compromised from storms and other events.

[1] City of Portland. https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/article/127469 (accessed March 25, 2018).

[2] WBDG. Extensive Green Roofs. http://www.wbdg.org/resources/greenroofs.php (accessed April 2, 2018).

[3] US EPA. “Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies- Green Roofs.” https://www.epa.gov/heat-islands (accessed April 2, 2018).

[4] NJ Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual – Chapter 2: Low Impact Development Techniques. http://www.njstormwater.org/bmp_manual/NJ_SWMP_2 print.pdf (accessed April 2, 2018).

[5] Native Bergen http://www.nativebergen.com/green-roof-grows-in-teaneck/ (accessed April 22, 2018).

[6] US EPA. “Green Roofs for Stormwater Runoff Control” February 2009. https://www.nps.gov/tps/sustainability/greendocs/epa%20stormwater-sm.pdf (accessed March 25, 2018).

[7] GSA. 2011. The Benefits and Challenges of Green Roofs on Public and Commercial Buildings. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/The_Benefits_and_Challenges_of_Green_Roofs_on_Public_and_Commercial_Buildings.pdf (accessed Sept 24, 2018).

[8] US EPA. Heat Island Effect: Using Green Roofs to Reduce Heat Islands. https://www.epa.gov/heat-islands/using-green-roofs-reduce-heat-islands (accessed March 25, 2018).

[9] Oberndorfer, Erica et. al. 2007. Green Roofs as Urban Ecosystems: Ecological Structures, Functions, and Services. Biosciencemag.org 57, no. 10. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/57/10/823/232363 (accessed March 25, 2018).

[10] James Hoff. “Reducing Peak Energy Demand: A Hidden Benefit of Cool Roofs.” TEGNOS Research. https://www.coolrooftoolkit.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Peak-Demand-Hoff-11.11.14.pdf (accessed March 25, 2018).

[11] Whole Building Design Guide. Extensive green roofs. http://www.wbdg.org/resources/greenroofs.php (accessed March 25, 2018).

[12] US EPA Heat Island Effect – Green Roofs http://www.epa.gov/heatisland/mitigation/greenroofs.htm (accessed April 2, 2018).

[13] City of Portland. “EcoRoofs.” https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/article/127469 (accessed March 25, 2018).

[14] GSA. 2011. The Benefits and Challenges of Green Roofs on Public and Commercial Buildings. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/The_Benefits_and_Challenges_of_Green_Roofs_on_Public_and_Commercial_Buildings.pdf (accessed Sept 24, 2018).

Related Strategies

Resources

- Center for Neighborhood Technology – Green Values Calculator

- New Jersey Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual – Chapter 2: Low Impact Development Techniques

- US EPA

- Gaffin, S. R., Kong, A.Y.Y., De Mel, J.M., and Rosenzweig, C. 2017. Green, White and Dark Roofs – The energy perspective. New York, NY, USA: Center for Climate Systems Research at Columbia University and NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

- The Sustainable Sites Initiative

- Whole Building Design Guide – Extensive Vegetative Roofs