Biophilic Design

Existing CommercialWhat is Biophilic Design?

Biophilic design is related to the concept of biophilia, a term popularized by biologist E.O. Wilson, that suggests connections with the natural world enhance human physical and mental well-being. [1] The biophilia hypothesis indicates that people have a biological affinity for nature, based on such an affinity’s evolutionary advantage. An affinity for the natural world can be broken down into nine categories representing different values and expressions of biophilia, including the natural world as a source of material utilization and exploitation, physical beauty and appeal, empirical

knowledge and understanding, communication and thought, exploration and discovery, bonding and companionship, mastery and control, moral and spiritual connection, and fear and repression.[2] Biophilic design, which incorporates connections to natural systems and materials into the built environment, creates an opportunity for exercising and strengthening biophilic values, which in turn, opens the door to physical, intellectual, and emotional benefits.

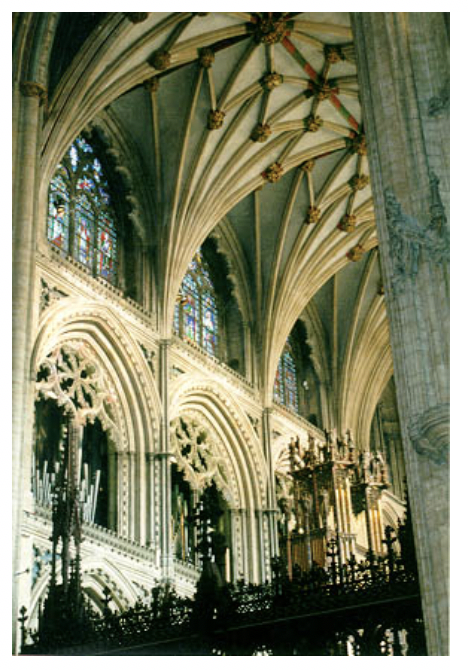

Figure 1- A cathedral has many biophilic elements in the way in which it manipulates light and space and air, and material and shape and form, and color (Source: http://www.stanford.edu/~dorris/photos/ely3.jpg).

Key Elements of Biophilic Design[3]

- Environmental features

- Natural shapes and forms

- Natural patterns and processes

- Daylight and open space

- Place-based relationships

- Evolved human-nature relationships

These biophilic design attributes are defined further in the book, “Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life” by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador.

How to Incorporate Biophilic Design

Specify biophilic design goals early in the design process and engage the entire project team. Biophilic design involves the use of local, natural materials, potted plants, courtyard gardens, views to nature, natural light and ventilation, water features, animals and aquariums, and blurring the boundaries between the building and the surrounding landscape (see Views and Operable Windows, Native and Adapted Plants, Daylighting, Natural Ventilation).

Studies show that fractal patterns found in nature and natural patterns such as “waves, leaves in a breeze, fish swimming in an aquarium, or a flickering fire,” captivate people’s attention and induce states of relaxation far better than spaces and views without “visual richness” such as blank, white walls or tree-less streets.[4] Look to incorporate patterns found in nature through representational artwork, ornamentation, biomorphic forms and use of natural materials such as wood and stone.

Example

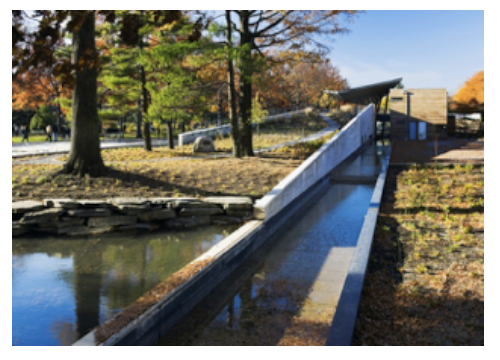

Sunlight and Water, Queens Botanical Garden (QBG) Visitor Center, Flushing, NY

The QBG Visitor Center illustrates biophilic design with the windows in the first-floor corridor, which capture the sun reflecting off the rainwater harvest feature that runs along the exterior of the building. Depending on the time of day and amount of sunlight, an occupant of the building can see patterns of sunlight reflected on the interior walls and ceiling. The interplay between sun and water connects people inside to the changes in the outdoor environment throughout the day.

Figure 2 – QBG Rainwater harvest feature (Source: Jeff Goldberg, Esto)

Benefits

Many studies document the benefits of a connection to nature in the built environment. For example, studies point to positive gains in workplace productivity through increased mental focus and attention, enhanced cognitive functioning, reduced stress levels, greater worker satisfaction, elevated moods, and less sick days; views to nature result in shorter recovery rates in hospitals, and daylighting increases sales in retail buildings and improves test scores and accelerates learning rates in schools.[5] For example, pain medication was requested 23 percent less with patients in hospital rooms with morning sunshine compared to rooms lacking natural light.[6] Another study showed that students with access to natural light from operable skylights improved 19-20% faster than students in classrooms without a skylight.[7]

Costs

Recent studies that quantify the benefits of biophilic design elements in the built environment help advance biophilic design from an add-on to an integrated design strategy and profitable pursuit.[8] One peer-reviewed study by Terrapin Bright Green, LLC (see Resources) measures and quantifies the cost-benefits of biophilic design on the following indicators of productivity:[9]

- Illness and absenteeism

- Staff retention

- Job performance (mental stress/fatigue)

- Healing rates

- Classroom learning rates

- Retail sales

- Violence statistics

Resiliency

Biophilic design can lead to a deeper connection to nature, which in turn, can foster an environmental ethic that supports ecological resilience by protecting the biological diversity of native plants and animals in a given area and enhancing the ability of the natural system to rebound after a disturbance. Common biophilic design features such as daylighting provide resiliency benefits by maintaining lighting levels for critical functions when the grid goes down due to environmental or other issues. The use of local materials supports local knowledge and resources for maintaining and rebuilding after storms. Natural materials such as stone provide strength and durability and also help in maintaining thermal comfort during power outages (see Thermal Mass). Biophilic design connects buildings to nature and links building systems to complex, natural systems that can adapt to changing conditions – a cornerstone of resiliency. Some of our most historic and beloved buildings incorporate biophilic design elements, supporting the notion that people and communities look to maintain and protect beautiful, timeless and inspiring buildings.

[1] International Living Building Institute. Biophilic Design Initiative. https://living-future.org/biophilic design-overview/ (accessed January 4, 2019).

[2] Kellert, Stephen. “Kinship to Mastery: Biophilia in Human Evolution and Development.” Island Press, Shearwater Books. Washington, D.C. 1997. Page 3.

[3] International Living Future Institute – Biophilic Design Initiative. https://living-future.org/biophilic-design-overview/ (accessed January 6, 2019).

[4] Terrapin Bright Green, LLC. The Economics of Biophilia – Why designing with nature in mind makes financial sense. Peer Review by Judith Heerwagen and Vivian Loftness https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/the-economics-of-biophilia/#front-matter (accessed Sept 28, 2018).

[5] Terrapin Bright Green, LLC. Biophilia – Why designing with nature in mind makes financial sense. Peer Review by Judith Heerwagen and Vivian Loftness https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/the-economics-of-biophilia/#front-matter (accessed September 28, 2018).

[6] Sole-Smith, Virginia. “Nature on the Threshold.” New York Times, September 7, 2006, Home and Garden section. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/07/garden/07bio.html (accessed September 20, 2018).

[7] Heschong, Lisa. Daylighting in Schools. California Board for Energy Efficiency. 1999. http://www.coe.uga.edu/sdpl/research/daylightingstudy.pdf (accessed September 20, 2018).

[8] Wilson, Alex. Biophilia in Practice: Buildings that Connect People with Nature. Building Green, July 2006. https://www.buildinggreen.com/feature/biophilia-practice-buildings-connect-people-nature

(accessed September 20, 2018).

[9] Terrapin Bright Green, LLC. Biophilia – Why designing with nature in mind makes financial sense. Peer Review by Judith Heerwagen and Vivian Loftness. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/the-economics-of-biophilia/#front-matter (accessed January 4 2019).

Related Strategies

Resources

- Biophilic Design – The Architecture of Life

- Heerwagen, Judith, Kellert, Stephen, Mador, Martin. Biophilic Design: Theory, Research, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. John Wiley.

- Kellert, Steven. 2005. Buildings for Life – Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection. Island Press.

- GSA Sustainable Facilities Tool – Biophilic Design

- International Living Future Institute – Biophilic Design Initiative

- Terrapin Bright Green LLC – The Economics of Biophilia – Why designing with nature makes economic sense

- Whole Building Design Guide – Psychosocial Value of Space