Native and Adapted Plants

New CommercialWhat are Native and Adapted Plants?

Native plant species thrive naturally in a particular region, ecosystem or habitat without direct or indirect human actions.[1] Adapted plants have evolved to the physical conditions such as soil, climate, and geology of a site but were not formally part of the natural ecosystem.[2] Invasive plants grow quickly and aggressively, often displacing native plants and adversely impacting native wildlife, local food sources, and pollination.[3]

Landscaping with plants that are native and adapted to the Mid-Atlantic geographic region nurtures a diverse and healthy ecosystem and saves time and maintenance costs. Diverse native habitats resist disease, reduce the need for synthetic pesticides, increase biodiversity and provide habitat for native wildlife, reduce stormwater runoff and mitigate flooding, and provide an alternative to the time-consuming, energy-intensive, and water-inefficient practices of lawn and turf care (see Turf Grass Reduction).

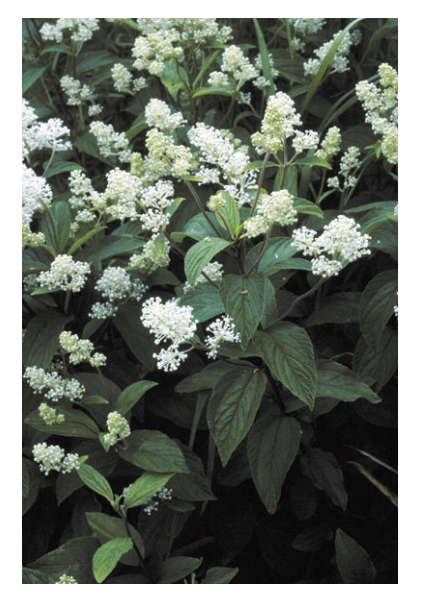

Figure 1 – Example of a plant native to New Jersey – New Jersey Tea Ceanothus americanus (Source: US EPA)

How to Incorporate Native and Adapted Plants

- Assess existing site conditions: Is the site sunny or shaded? Flat or sloped? Is soil tight (clay) or loose (sand)? Drainage (quick or slow)? What is the existing vegetation on the site?

- Research local nurseries that specialize in native plants and contact nurseries in advance to obtain availability lists.

- Choose plants appropriate for the site conditions. The Native Plant Society of New Jersey provides a list of NJ native plants by County. Some projects may be eligible for the Wildlife Habitat Incentives Program. Resources such as Jersey-Friendly Yards offer plant information and an easily searchable plant database.

- Site preparation: minimize disturbance to the natural landscape, test the soil, and amend the soil with compost when necessary.

- Install plants and water regularly until established (see Water-Efficient Landscaping).

- Create and implement a long-term land management plan for maintenance, including integrated pest management (see Integrated Pest Management).

Benefits

Incorporating native and adapted plants:

- Reduces the amount of water used in landscaping.

- Reduces use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, which contaminate water from runoff and pose a threat to humans, pets and the environment.

- Increases wildlife habitat and biodiversity.

- Reduces stormwater runoff and improves stormwater quality (replacing lawns and turf with natural vegetation maximizes stormwater absorption).

- Reduces the amount of landscape waste often generated from routine maintenance of a manicured landscape.

- Increases appreciation for regional, natural resources and sense of place.

- Saves maintenance cost (once established, native plants can be less costly to maintain than some non-native landscapes).

Costs

All landscapes require regular maintenance and a long-term maintenance plan. The cost of maintaining any landscape depends on the type of plants and the expectations for that landscape. Once established, native landscapes maintenance costs may be lower than some non-native landscapes.

Resiliency

In coastal areas, tidal estuaries and along rivers, native and adapted plants act as an essential buffer to encroaching water during flood periods while acting as a routine defense against beach erosion. For example, American Beachgrass considered one of the best lines of shoreline defense against storms, may also help prevent increasing levels of brackish water from infiltrating water tables close to a salt-water body.[4] In general, the root systems of native plants can reduce runoff and mitigate flooding.[5] In the event of droughts, water-efficient landscapes designed with native and adapted plants add layers of protection against water scarcity. Native plants also increase biodiversity and provide habitat for native wildlife necessary for a healthy and resilient ecosystem that can better rebound after a disturbance.[6]

[1] Audubon. Plant Natives. http://web4.audubon.org/bird/at_home/PlantNativeSpecies.html (accessed April 2, 2018).

[2] Swearingen, J., K. Reshetiloff, B. Slattery, and S. Zwicker. 2010. National Park Service and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. “Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas.” Washington, D.C. http://www.nyis.info/user_uploads/files/Plant%20Invaders%20of%20Mid-Atlantic.pdf (accessed March 14, 2018).

[3] PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. “Invasive Plants” http://www.dcnr.pa.gov/Conservation/WildPlants/InvasivePlants/Pages/default.aspx (accessed March 14, 2018).

[4] Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. StormSmart Properties Fact Sheet 1: Artificial Dunes and Dune Nourishment. http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/czm/program-areas/stormsmart-coasts/stormsmart-properties/fs-1-dunes.html (accessed March 14, 2018).

[5] USDA Forest Service. Native Gardening. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/Native_Plant_Materials/Native_Gardening/index.shtml (November 9, 2018).

[6] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Why Native Plants. https://www.wildflower.org/about/why-native-plants (accessed November 4, 2018).

Related Strategies

Resources

- Center for Urban Restoration Ecology – A Collaboration between Rutgers University and Brooklyn Botanic Garden

- Green Values Stormwater Toolbox

- Jersey-Friendly Yards

- Native Plant Database

- The Native Plant Society of New Jersey

- Rutgers – New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station – Incorporating Native Plants

- Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas

- Sustainable Sites Initiative

- USDA and NRCS Aberdeen Plant Materials Center – Plants for Riparian Buffers

- USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service

- US EPA Greenscapes